The Power Of Thinking Irrationally

I am intrigued by the idea that there may be more powerful ways to think, and by thinking about thinking itself we can upgrade our thought processes. But I am also intrigued by things that go against the conventional wisdom. So I was very curious recently to see Tyler Cowen’s criticism of the rationality community:

I would approve of them much more if they called themselves the irrationality community. Because it is just another kind of religion. A different set of ethoses. And there’s nothing wrong with that, but the notion that this is, like, the true, objective vantage point I find highly objectionable.

The idea of an irrationality community fascinates me. Who could possibly support irrationality? Is irrationality good for something? Could there be irrationality enthusiasts, eagerly swapping techniques for the most effective sort of irrationality?

What exactly is irrationality? From Wikipedia:

Irrationality is cognition, thinking, talking or acting without inclusion of rationality. It is more specifically described as an action or opinion given through inadequate use of reason, or through emotional distress or cognitive deficiency. The term is used, usually pejoratively, to describe thinking and actions that are, or appear to be, less useful, or more illogical than other more rational alternatives.

Actions that are backed by inadequate reasoning. Perhaps even actions taken without evidence, based purely on emotion. It sounds bad at first, but actually I think it is very valuable to act this way sometimes.

I don’t think rationality is bad per se. It’s more like, there are several modes of thinking. Sometimes it’s better to think in “rational mode”, and sometimes it’s better to think in “irrational mode”. Depending on the situation, you might want to switch from irrational to rational, like an MMA fighter switching from boxing to jiu-jitsu. (It’s similar to Thinking Fast And Slow, but I don’t necessarily think the irrational mode needs to be faster.)

So I mentioned that I thought rationality was overrated to someone, and they remarked that they were surprised, because I am a “mathy” person, that I would be the sort of person to dismiss rationality. But I think math is a great example where you want this sort of dual, sometimes-rational-sometimes-irrational thinking. Sometimes you work very rationally on a math problem - you see x + 2 = 5, you want to solve for x, you recall an algorithm for this, you execute the steps one by one, the end. But for a tricky math problem, you might actually spend most of the time without reasons for what you do. You can just stew around in more of an “irrational brainstorming” mode, where you don’t have reasons or evidence, you just have loose fuzzy emotional heuristicky thinking, until you seize on what you think is a solution. And then you can toggle into “rational mode” to check the solution for validity, but still you spent the vast majority of your time in “irrational mode”.

Let me go through an example. Here’s a math puzzle that someone just randomly asked to me while we were walking around once. It’s a question: can you pick five lattice points and connect each pair with line segments so that no other lattice points are on those line segments?

If you don’t know what a lattice point is, it’s just the points (x, y) where x and y are both integers. So the lattice points look like this:

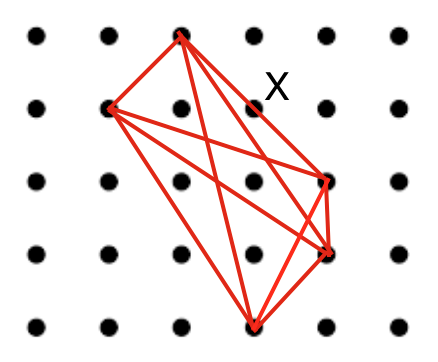

And a solution to the problem would look like this…

…except that the line segment marked with an X contains another lattice point. So in fact this isn’t a solution, and if you keep poking around by trial and error you will find it quite difficult to find a solution.

(If you want to solve this problem without me really getting spoilery, do it now without reading any further.)

This sort of problem doesn’t require any advanced math, but it doesn’t map to any sort of math problem you drilled on in high school. Some people will just read this problem description, and then, nothing pops into their head. Or they trial and error a few times, fail, and then don’t know what else to do. They will just stare blankly at the problem and not know what to think about next.

When this happens to you, rational thinking is worthless. If you don’t have any evidence to start out with, you can’t start making rational conclusions. So when you find yourself totally stuck, thinking no thoughts at all, that is your mental cue to switch into irrational mode. You’re too far away to grapple - use boxing instead of jiu-jitsu.

To think irrationally about this problem, just don’t worry about logical connections making sense. Feel out for any emotions about the problem that you have and assume they are axioms. Think of other things that this reminds you of. If A implies B, and you know B is true, imagine for a second that that implies A. Let yourself use some logical fallacies. Just see if those lead you somewhere interesting.

At this point, I would come to irrational conclusions like:

-

I tried to do it several times and could not. Therefore it is impossible.

-

Since the graph connecting 5 points is nonplanar, and these lattice points are in the plane, it also cannot be embedded into lattice points.

-

The number 5 is very ugly so it causes the math to fail.

-

Lattice points are made up of squares, and the square’s favorite number is 4, so 4 can work but not 5.

-

You can jam four things in there but there just isn’t enough room to jam five things in there.

These conclusions are not based on evidence, they are not based on logical arguments, they are not really logically correct, they are tainted with all sorts of emotions and biases, and at least one is just totally wrong. But they are useful because they are maybe correct, more likely than 0% chance correct, and they give you sparks to continue. And they are not just useful inside one person’s head - if you have multiple math-problem-solvers brainstorming, it’s useful to share these half-thoughts with each other. You have to trust your collaborators to be fairly intelligent. But when you are in a group you trust, it can really help you to accept some irrational conclusions. And that principle goes beyond solving math problems.

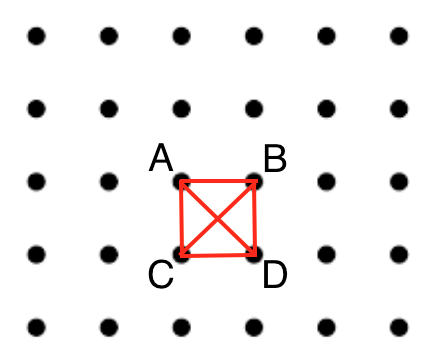

Anyway, some of these irrational conclusions can be the seed of a rational proof. Perhaps the “not enough room to jam it in there” reminds you of the pigeonhole principle and the answer comes to you in a flash. Or perhaps the five-versus-four and squares-are-beautiful aspects lead you to think about a very simple way to solve it for four points, and ponder deeply why this particular solution can’t be extended to five points:

Why can’t this be extended to five points? This example is simple enough that you can try extensions in your head and label each new point by which of these four original points it conflicts with. You will get lattice points labeled like:

A B A B A B

C D C D C D

A B A B A B

C D C D C D

A B A B A B

You can’t have more than one A in your five points, and actually that is true even if you didn’t start with the simple square, if you think about it.

(I’m not quite sure how much my blog audience would like me to spell out the math here, but perhaps I’ll leave it at this.)

I suspect that most people who are trying hard to get better at math, or at similar skills like programming problem-solving, are actually not struggling with the “rational” part, of rigorously proving something works. They are struggling with the “irrational” part, of how do they make progress when they are unable to make rational conclusions. So don’t feel like it’s dirty or inappropriate. Thinking irrationally can be another useful tool in your toolbox. Embrace it, and let me know what irrational techniques work for you.