Visiting SFMOMA

Near the end of Proust’s In Search Of Lost Time, the main character realizes that his own life can be the inspiration for a great work of literature. During this epiphany, Proust makes a brief digression to talk about art, and how to appreciate art you really need to pay attention not only to the art itself, but also the memories it triggers or the impression that it makes in you, the viewer.

Let me quote a few sentences.

Even where the joys of art are concerned, although we seek and value them for the sake of the impression that they give us, we contrive as quickly as possible to set aside, as being inexpressible, precisely that element in them which is the impression that we sought, and we concentrate instead upon that other ingredient in aesthetic emotion which allows us to savour its pleasure without penetrating its essence and lets us suppose that we are sharing it with other art-lovers, with whom we find it possible to converse just because, the personal root of our own impression having been suppressed, we are discussing with them a thing which is the same for them and for us. Even in those moments when we are the most disinterested spectators of nature, or of society or of love or of art itself, since every impression is double and the one half which is sheathed in the object is prolonged in ourselves by another half which we alone can know, we speedily find means to neglect this second half, which is the one on which we ought to concentrate, and to pay attention only to the first half which, as it is external and therefore cannot be intimately explored, will occasion us no fatigue. To try to perceive the little furrow which the sight of a hawthorn bush or of a church has traced in us is a task that we find too difficult. But we play a symphony over and over again, we go back repeatedly to see a church until - in that flight to get away from our own life (which we have not the courage to look at) which goes by the name of erudition - we know them, the symphony and the church, as well as and in the same fashion as the most knowledgeable connoisseur of music or archaeology. And how many art-lovers stop there, without extracting anything from their impression, so that they grow old useless and unsatisfied, like celibates of art!

The rest of the paragraph is pretty good, too.

Anyway, I used to think that when you looked at art you should use some sort of “evaluating art” skill, the way I would look at the design for a new database and think about whether it seemed like a good database design or not. And it just seemed like I lacked this skill, or found the development of this skill uninteresting. After reading this book I was curious to try out this “Proustian” way to appreciate art, where instead of wondering whether the art was good or not, you just look at it and if it triggers any memories, you think about those memories, see what things you can remember that you haven’t thought about in years, see if the art relates to those memories and if you can dig in somehow.

So last weekend I took a trip to SFMOMA with my 9-year-old son, and I really enjoyed this exhibit of American abstract art, which I never really appreciated very much before.

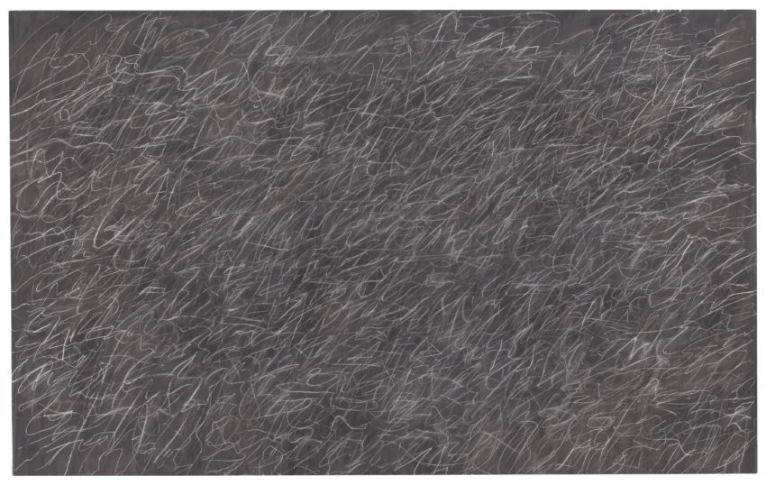

This piece reminds me of the blackboard in the first math class I took in college. The professor would get really emotionally engaged in writing things on the blackboard while talking about them, and in the process he would seem to stop paying attention to the blackboard itself. Often it would be impossible to distinguish different Greek letters, or different parts of a formula would run into each other.

Rather than completely erase the board, the professor would sort of quickly swipe an eraser and then start writing something else. The blackboard became like the catacombs beneath Mexico City, new buildings constructed on top of the ruins of past generations, with the clever archaeologist able to discern layers of different lemmas and corollaries.

It’s like the subject itself, abstract algebra. Theorems about rings, laid on top of theorems about fields, on top of integers, on top of groups, all above a historical process of figuring this stuff out that resembled the eventual outcome but shuffled around and with a bunch of false starts mixed in there.

Meanwhile, my son enjoyed the sculptures that looked like the sort of armor a bug monster would wear. The only flaw of the trip was the cold and terrible pizza from the kid’s menu at the cafe. Next time, I will encourage him toward the chicken tenders.