How to 51% Attack Bitcoin

The core security model of Bitcoin is that it is very expensive to generate blocks of transactions. This means it is very expensive to attack Bitcoin by creating fraudulent transactions. Bitcoin miners can afford to invest a lot of money in hardware and electricity, because they are algorithmically rewarded when they do generate a new block.

Over time, the mining rewards decrease. Next year, in May 2020, the mining rewards will be cut in half. Eventually, there will be no more Bitcoin given as a block subsidy to miners, and the only payment to miners will be transaction fees. This naturally leads to some questions. Will Bitcoin still be secure when the mining rewards are cut in half next year? Will Bitcoin always remain secure, even after all the mining rewards run out?

Eli Dourado wrote a good analysis of this issue recently. He concludes, “At some point, the block subsidy will not be enough to guarantee security.” But I think we can be more specific. The way to analyze the security of Bitcoin is to look more closely at how a bad guy would attack it. So let’s do that. Our goal is to develop specific metrics for measuring the security of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies.

How much does it cost to attack Bitcoin?

The most straightforward way to attack Bitcoin is the 51% attack. Anyone can roll back all Bitcoin transactions that were confirmed over a recent time period. You just need more hash power than Bitcoin miners spent over that period. You can use that hash power to generate an alternate blockchain, and the Bitcoin algorithm guarantees that miners will respect your new blockchain over the “original” one. It’s called a “51% attack” because you need to have more than half of the hash power over some time period to perform it.

How expensive is this? A decent approximation is that the cost of generating an alternate blockchain is equal to the revenue made by miners. From blockchain.com we can get a chart of daily mining revenue over the past year:

Since miners are profitable, and this is how much money miners are making, this should be an upper bound on the cost of hashpower. It’s pretty volatile, somewhere between $5 million and $25 million per day. I find it easier to think in terms of hours, so somewhere from $200,000 to a million dollars an hour. (In practice, you cannot simply buy a million dollars worth of hashpower over a single hour. But the illiquidity of this market can’t really be relied on for security.)

So, a reasonable estimate for October 2019 is that it costs about a million dollars to roll back one hour of Bitcoin transactions.

How profitable is it to attack Bitcoin?

A million dollars sounds like a lot, but in the context of a financial system that processes billions of dollars, is it really a lot? The way to analyze security is to compare the cost of an attack with the profit of an attack. If profit is greater than cost, an attack is possible, so the system is insecure.

The way that a 51% attack makes money is by allowing the attackers to do a double spend. You spend your Bitcoin on something, then you use the 51% attack to roll back the blockchain, so you have your money again. You then spend that money on something else. So, you doubled your money.

“Spend” makes it sound like you are interacting with a merchant, like you are spending your Bitcoin on buying a pizza. In practice, criminals are not trying to spend a million dollars to get two million dollars worth of pizza. Rather than spending Bitcoin to get some consumer good, it makes more sense for an attacker to exchange their Bitcoin for some other sort of asset. The most logical asset is a different form of cryptocurrency. Let’s say Ethereum.

So the timeline for an attack could look like this:

- Start off with $X worth of Bitcoin in wallet A

- Move the Bitcoin from wallet A to wallet B

- Exchange all the Bitcoin in wallet B for $X of Ethereum

- 51% attack Bitcoin. Roll back the A -> B transaction. In the new chain, move the Bitcoin from wallet A to wallet C.

- The attacker now owns both $X of Ethereum and $X of Bitcoin in wallet C

The primary victim of a 51% attack is the exchange. The exchange delivered the Ethereum, but the transaction sending them Bitcoin is no longer valid.

The critical steps in analyzing profitability are steps 3 and 4. How long does it take to exchange the Bitcoin for Ethereum? How much can be exchanged by an untrusted attacker? If an untrusted attacker can exchange $2 million of Bitcoin for $2 million of Ethereum in an hour, and then spend $1 million to revert that transaction, the attack is profitable.

Some people have proposed security heuristics, like that mining revenue should be some percentage of the total transaction volume, or the total market cap. When we look at the mechanics of an attack, though, total transaction volume and total market cap aren’t relevant. The key question is how fast an attacker can exchange $X of Bitcoin for another asset. For this attack to be profitable, X has to be higher than the cost of the rollback, which is roughly equal to mining revenue over the rollback time.

For security against 51% attacks, the amount an attacker can exchange must be lower than mining revenue during the duration of the exchange.

In particular, Bitcoin’s security depends inversely on how fast it can be exchanged.

How fast can you exchange Bitcoin for another asset?

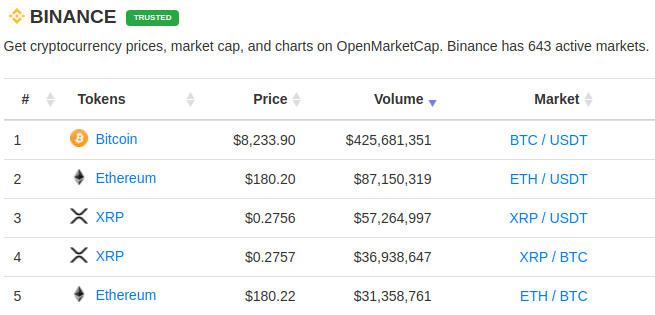

Binance is probably the largest exchange right now. Let’s use them as an example exchange - most exchanges have similar policies, but smaller volumes.

Binance recently updated their policy to consider transactions finalized within two blocks for Bitcoin, which is about 20 minutes, and 12 blocks for Ethereum, which is roughly three minutes. So the deposit and withdrawal phases of the exchange would take maybe half an hour.

The more time-consuming part might be the actual exchange of Bitcoin for Ethereum. Openmarketcap can show us the daily trading volume on Binance:

Per hour, that’s about $20 million of BTC / USDT changing hands, and $4 million of ETH / USDT. You wouldn’t be able to exchange $10 million of BTC to ETH in that hour without totally disrupting the market. If you were exchanging $100,000, that would just be a drop in the bucket. It’s hard to say without analyzing the order books more closely how much extra volume the exchange could support, but let’s estimate that a single trader could take up 10% of the total volume.

With this estimate, exchanging into ETH isn’t going to work. But you could exchange $4 million of BTC to USDT in two hours.

I expected when writing this post that I would conclude that Bitcoin is currently fundamentally secure. It doesn’t really seem that way, though!

The timeline for this hypothetical attack looks like this:

- Start off with $4 million of Bitcoin in wallet A

- Move the Bitcoin from wallet A to wallet B

- Deposit Bitcoin from wallet B into Binance

- Exchange it for USDT (takes about 2 hours)

- Withdraw the USDT

- 51% attack Bitcoin, rolling back the chain 2.5 hours, moving the contents of wallet A to wallet C.

- The attacker now has $4 million of Bitcoin in wallet C and $4 million of USDT

The attacker in this scenario spent $6.5 million to get $8 million. Binance is out $4 million, and $2.5 million got burned on redundant mining.

Why isn’t this attack happening right now?

There are three big assumptions that underly this analysis. The biggest assumption is that it is possible to acquire a large amount hash power for a short period of time. In practice, there is nobody who can sell you a million dollars worth of hash power over a single hour.

Can we rely on a market for hash power continuing to not exist? Maybe. This is essentially relying on large miners being unwilling to rent out their mining capacity. It doesn’t seem like the ideal foundation for security.

Altcoins are more at risk in this respect, because it is easier to acquire the amount of hash power needed to attack an altcoin.

The second big assumption is that the exchange will permit an untrustworthy attacker to quickly exchange a large amount of currency. If an exchange can prevent their customers from committing fraud in traditional ways, like knowing who they are and trusting normal law enforcement to prevent fraud, then the risk of a 51% attack is mitigated. Exchanges also might not let you deposit a large sum and immediately trade it. To avoid this, attackers might have to split these trades among multiple accounts or multiple exchanges.

Smaller exchanges that evade KYC regulation are probably more at risk here. Smaller exchanges might not have the volume to support an attack on Bitcoin, though, so this also means that altcoins are more at risk than Bitcoin is.

The final big assumption is that the value of cryptocurrency would not be affected by the attack. Perhaps a successful attack on Bitcoin would make the world world stop believing in Bitcoin and make all cryptocurrencies worthless. This isn’t something I would want to rely on, but it does mean, again, that altcoins are more at risk. If the 10th most popular cryptocurrency was attacked, it might have no impact on the price of Bitcoin.

All of these practical issues imply that altcoins are much easier to 51% attack than Bitcoin.

Altcoins are the canaries in the coal mine.

So which altcoins are in the most danger? This analysis only applies for proof-of-work coins, so whatever your opinion is on non-proof-of-work cryptocurrencies like XRP or EOS, this isn’t going to be a criticism of them.

Our rule for security is that a cryptocurrency becomes insecure when an attacker can trade more than mining revenue. We don’t know exactly how much a single attacker can exchange, but a reasonable assumption is that it is a certain fraction of the total exchange volume. This suggests that we can define a “danger factor” for cryptocurrencies. Call it D:

D = exchange volume / mining revenue

Or equivalently:

mining revenue = 1/D * exchange volume

Our previous security rule was that if an attacker can exchange more than mining revenue, the cryptocurrency is insecure. With this definition of D, we can rephrase that as:

If an attacker can exchange 1/D of total exchange volume, the cryptocurrency is vulnerable to a 51% attack.

A large value of D indicates that a currency has a high vulnerability to a 51% attack. D doesn’t have the same meaning for Bitcoin, since exchanging out of Bitcoin is limited by the volume of the altcoin, rather than the volume of Bitcoin itself. But for altcoins, D seems like a good proxy of risk.

The nice thing about D is that we can determine it from public information. I gathered some data for this table for ten of the larger proof-of-work altcoins. Mining revenue I got from bitinfocharts, although you have to click around a lot to get it. Exchange volume I got from openmarketcap. The data is just for today, October 7 2019.

| Cryptocurrency | Daily Exchange Volume | Mining Revenue | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethereum | $234,357,917 | $2,502,075 | 93.6 |

| Bitcoin Cash | $45,483,383 | $412,722 | 110.2 |

| Litecoin | $52,306,855 | $400,713 | 130.5 |

| Bitcoin SV | $2,426,079 | $143,455 | 16.9 |

| Monero | $7,260,841 | $91,483 | 79.3 |

| Dash | $2,639,938 | $121,673 | 21.6 |

| Ethereum Classic | $7,188,482 | $121,921 | 59.0 |

| Dogecoin | $451,196 | $35,536 | 12.7 |

| Zcash | $4,571,311 | $266,702 | 17.1 |

| Bitcoin Gold | $251,734 | $14,783 | 17.0 |

This is just a snapshot of a single day of activity, so treat it as an estimate rather than a firm basis for decisionmaking, but based on this metric, Litecoin is the most vulnerable to a 51% attack, followed by Bitcoin Cash.

Ethereum is the next most vulnerable, so it is fortunate they are working on proof-of-stake. The cost of attacking the network should be significantly larger than the cost of attacking a proof-of-work network, relative to mining revenue.

For Bitcoin, the exchange is limited by the asset on the other end, rather than bitcoin itself. I would estimate its danger factor as D = 30, looking at the BTC/USDT exchange volume rather than the entire BTC exchange volume.

Conclusion

The risk of 51% attacks is real. Even today, for the security of Bitcoin we are trusting miners to not collude with each other, and trusting exchanges to catch fraudulent transactions.

However, the risk is worse for altcoins. Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Ethereum, Monero, and Ethereum Classic are especially at risk.

I believe that we will need to upgrade the algorithms behind popular cryptocurrencies to prevent 51% attacks. Ethereum moving to proof-of-stake is a good example. It might make sense to change Bitcoin’s consensus algorithm at some point, but there’s a lot at stake, so it makes sense to move conservatively. Let’s see what happens with the proof-of-work altcoins. If they do get attacked, perhaps it will make sense to alter the Bitcoin algorithm.