-

Higher! Higher!

I read a decent amount of fiction and I also read a decent amount of nonfiction. But nowadays I really read a lot of kids’ books.

At first reading to children seems like, well you get some kids’ books and you just go read them a book, that’s all there is to it. The medical establishment strongly recommends it and it seems like reading to children might also be one of the key ways that parents pass on their advantages to their children, so read books to your kids. That stuff makes it seem like reading to kids is a “yes or no” thing. If you read to your kids then you are a good parent and if you do not you are a bad parent. So at first I just thought, “Okay I’ll do it!”

But after a while I started thinking, what am I trying to achieve with this reading experience? What should I be focusing on? What should I be trying to get the kid to do? And especially, what sort of book is a good one to read to kids?

Rather than lay out some abstract principles, I am going to claim that the single best book for the 0 years old to 2 years old range is Higher! Higher!.

At this point you might be thinking, is this guy seriously writing a book review that is orders of magnitude longer than the book itself? The answer is yes.

But let me explain why this book is a good one. I have different tactics to suggest for the different parts, and I will quote literally all the words in the book as we go along.

Rising Action

As an adult, you might find the first nine pages somewhat repetitive.

- The cover shows a girl, probably named Tia, on a swing, saying:

Higher! Higher!

- The title page shows the girl’s father pushing the girl, and it repeats the title of the book:

Higher! Higher!

- On the first “real page” of the book, the father is pushing the girl already a dangerously high amount, with the swing-ropes already above horizontal, and yet the girl requests:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is approximately the same height as a giraffe, and saying:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is approximately the same height as a building. A balloon, dog, cat, mountains, and a game of checkers are visible. She requests:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is approximately the same height as the previously-visible mountain. There is a distant airplane. She is saying:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is hanging out with two airplanes, and continues to request:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is in space, maybe low earth orbit. There’s a rocket in the distance, and she says:

Higher! Higher!

- The girl is now swinging higher. She is right next to the rocket, which naturally has a monkey inside. The girl demands:

Higher! Higher!

Okay, so you probably detect a pattern here. The first eighteen words are all the word “Higher”. This might drive you nuts at first. But I think it is a good thing.

The point of reading books to a kid is not really to get them used to the process of listening to a book being read. It’s to get them excited about reading books themselves. And I do not think there is an easier book for a small child to read than this book. If you can only remember one word in your whole brain, as long as it’s the word “Higher”, you’re going to be able to follow along with a significant chunk of this book. Even read entire pages. Which is pretty exciting if you’ve never done that before, in your life.

Another piece of good design is the page-to-page continuity. For adults it is taken for granted that when you turn the page of the book, the next page is supposed to represent the same story, but just a little bit more in the future. For little kids, that isn’t necessarily obvious. But when you see a distant airplane, the girl requests “Higher”, and then the airplane is close up, that mapping becomes a bit more clear. As the reader you can either engage with this, talking a bit about the stuff in the picture before you turn the page, or skip through it, depending on your mood.

A final aspect of this first phase of the book that I really like is that the main character is a girl, and the plot includes many “traditionally boy” things, like airplanes, traveling to outer space, and a rocket.

Climax

Now comes the part to really stress your toddler’s reading skills. Different words. The climax is spread over three pages.

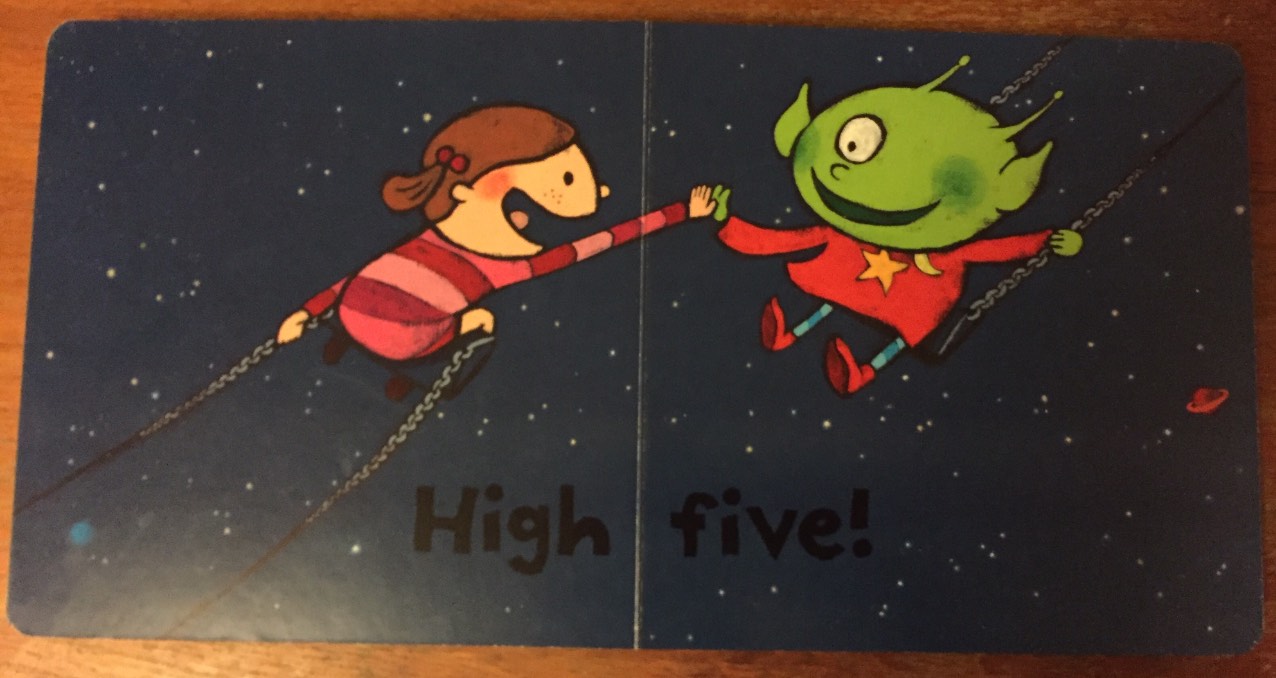

- The girl finally swings as high as she can swing, and sees… an alien kid who is also on a swing.

Girl: Hi! Alien: Hi!

- The girl and alien exchange a high five.

High five!

- They bid a fond farewell.

Girl: Bye! Alien: Bye!

The neat thing about this exchange is that each of these utterances has an associated hand gesture. I find it is easier to teach little kids words when they come with an associated “thing to do”. So you can wave hi, do a high five with your kid, and wave bye.

High fives are particularly underrated. At some point you can explain where the “five” comes from and get them into the math of having five fingers a little bit. Children seem to love it. It’s hard to believe the high five was only invented in the late 70’s.

An interesting question is whether this alien is male or female. Or “other”. I like to ask my kids to see what they think.

Denouement

Three mercifully wordless pages follow. The girl swings back down into the atmosphere, towards the playground, and is caught by her father. On the very last page, the girl turns to her father and has a last request:

Again!

Of course, your child is quite likely to interpret this “Again!” as a reminder, that they should also turn around and ask you plaintively, “Again?”

Such a clever engagement hack by the author. Like the Netflix widget that just quietly nudges you to watch the next video in the series. But this time, it’s a good thing, right? Because reading to your kid is good for them and you want to get them excited to read another book?

So there you have it. Higher! Higher! is a strong book for small children. The key is that you can do more than just read it to them. You can get them engaged with the words, and nudge them bit by bit into reading it themselves, even if they have never done that with any book before.

- The cover shows a girl, probably named Tia, on a swing, saying:

-

Why Uber Culture

Usually journalists writing about Silicon Valley have a hard time getting deep enough into the subject to keep me interested. But I really liked The Everything Store by Brad Stone, which covered the rise of Amazon. So I was excited when I saw that Brad wrote another book about the tech scene, The Upstarts, which focuses on Uber and Airbnb.

I feel like I already heard a lot of the “Airbnb legend” via the YCombinator mafia in one way or another, but most of the Uber stuff was new to me. So as I read it, I was trying to do this Straussian reading thing and think, what secrets about Uber are hidden within this book?

This book has a wealth of anecdotes - let’s investigate some of them.

Anecdote 1: Fighting San Francisco

First off, four months after it launched, back when Ryan Graves was the CEO, the California and San Francisco government together tried to shut down Uber:

Four months after the launch, when Graves was at a board meeting at First Round Capital with Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, four government enforcement officers walked into the tiny UberCab office. Two were from the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulated limousines and town cars, and two were from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which regulated taxis. The plainclothes officers flashed badges, and then one of them held up a clipboard with a cease-and-desist letter and a large, glossy head shot of a smiling Ryan Graves. Waving the photograph around the room, he demanded: “Do you know this man?”

Presumably most companies respond to a cease-and-desist from the government by ceasing and desisting. For Travis Kalanick this reminded him of his time with Scour and so his reaction was:

“For me that was the moment where I was like, for whatever reason, I knew this was the right battle to fight.”

“The great thing is I’ve seen this before,” he said. “I thought, Oh, man, I have a playbook for this. Let’s do this thing. When that happened, it felt like a homecoming.”

After some stressful legal battle, Uber got to keep operating their service without any changes. Meanwhile, competitors like Taxi Magic and Cabulous kept obeying the previous rules.

Anecdote 2: Fighting Washington, D.C.

In Washington, D.C. the taxi industry was powerful and a city councilwoman proposed a law that would prevent Uber from lowering prices to compete with taxis:

The regulations, added to a broader transportation bill, would give Uber legal sanction to operate. But they also added a price floor, which required Uber to charge several times the rate of a taxicab.

Uber’s lobbyists wanted to compromise; Uber’s leadership wanted to fight.

He supplied the phone numbers, e-mail addresses, and Twitter handles of all twelve members of the DC city council and urged his customers to make their voices heard. The next day he posted a public letter to the council members, writing ominously, “Why would you so clearly put a special interest ahead of the interests of those who elected you? The nation’s eyes are watching to see what DC’s elected officials stand for.” Mary Cheh was taken aback by the ferocity of the response. Within twenty-four hours, the council members received fifty thousand e-mails and thirty-seven thousand Tweets with the hashtag #UberDCLove.

DC ended up allowing Uber with no restrictions. Internally, Uber codified this strategy, with a principle called “Travis’s law”:

“Our product is so superior to the status quo that if we give people the opportunity to see it or try it, in any place in the world where government has to be at least somewhat responsive to the people, they will demand it and defend its right to exist.”

Uber doesn’t actually publicly promote this law. But they worked with Brad Stone, they gave him a lot of access, and Brad’s calling it “Travis’s Law” in this book. So it has to be what Travis and a big chunk of Uber really believes, right? And it doesn’t sound that bad on the face of it, does it?

The one part of this law which feels a bit roundabout is the phrase, “any place in the world where government has to be at least somewhat responsive to the people”. What does that mean, exactly? Does that just mean “a democracy”? It seems like it is trying to be a bit more expansive and include not just democracies but also societies that are half democratic or even “somewhat” democratic.

So flip that around. If you believe in Travis’s Law, and you notice that Government X does not allow Uber, what do you conclude - that Government X must not even be “somewhat” a democracy?

Anecdote 3: Following The Rules

I kind of knew about Uber fighting the government a lot. What I didn’t realize before reading this book is that there were times when Uber took the strategy of “not fighting the government”.

In particular, in 2012 Uber required every driver to be commercially licensed. At the time, that was a clear legal requirement, and even Uber didn’t want to fight that law. When Jason Calacanis asked Travis if he would consider using unlicensed drivers:

Kalanick fervently believed that services using unlicensed drivers were against the law — and would get shut down. “It would be illegal,” he said on the podcast This Week in Startups. “Unless the driver had what’s called a TCP license in California and was insured.”

“You don’t want to get into that kind of business?” asked host Jason Calacanis, the Uber angel investor.

“The bottom line is that we try to go into a city and we try to be totally, legitimately legal,” Kalanick replied.

At the time, Lyft was a small competitor, but they were willing to break that law. A year later, in 2013, the California government gave up their fight against Lyft, and Uber realized they had made a key mistake.

Travis Kalanick had watched, waited, and even quietly agitated for Lyft to be shut down. Instead, they spread, undercutting Uber’s prices. Now that their approach had been sanctioned, Kalanick had no choice but to drop his opposition and join them. In January 2013, Uber signed the same consent decree with the CPUC and turned UberX into a ridesharing service in California, inviting nearly anyone with a driver’s license and proof of insurance, not just professional drivers, to open his or her car to paying riders.

Et Cetera

There’s a lot more in this book and it’s really a fascinating story. I could have written a section for Fighting New York City and Fighting London. And half the book is about Airbnb! So if you’re interested in this sort of thing I really recommend buying The Upstarts.

To me, this book explains Uber’s culture. At every turn, they were rewarded for breaking the law, and punished for obeying the law. A culture that can survive that Pavlovian conditioning seems dangerous. And yet a hundred years of Taxi Magic competing with Cabulous may have just led to nothing. Perhaps Uber is not the startup we need, but the startup we deserve.

-

Music in Ancient Greece

As part of my quest to understand Straussian reading I have been reading The Republic. Written by Plato 2400 years ago. Allegedly this is a good book to read deeply because Plato had a lot of thoughts on society which he was trying to sneak past the censors. Which makes sense because the book is all about Socrates talking about how he thinks the government should be set up, and Socrates got executed for… something. Apparently the precise rationale for why Socrates got executed has been lost in the mists of time. Or just immediately deleted by those censors.

Anyway, if I were Plato I’d be pretty worried about saying something inappropriate in a book too. I would not be surprised if Plato were veiling some of his true beliefs here. I’ve been reading through it and thinking a whole lot about it while I’m reading it, trying to get all esoteric, and it does seem more interesting than when I read it more lazily back in high school.

One thing that surprised me is how much talk about music there is in The Republic. If I were writing about the ideal form of government nowadays, I would take it for granted that music was pretty irrelevant. The Constitution doesn’t talk at all about what sort of music leads to the ideal form of government.

But the Socratic theory of good government is way more focused on, first we need to think of what sort of people are good leaders. And then we need to figure out how our society can educate those qualities into people. Socrates brings up music here immediately:

“What is the education? Isn’t it difficult to find a better one than that discovered over a great expanse of time? It is, of course, gymnastic for bodies and music for the soul.”

“Yes, it is.”

“Won’t we begin educating in music before gymnastic?”

“Of course.”

“You include speeches in music, don’t you?”, I said.

“I do.”

“Do speeches have a double form, the one true, the other false?”

“Yes.”

“Must they be educated in both, but first in the false?”

“I don’t understand how you mean that,” he said.

“Don’t you understand,” I said, “that first we tell tales to children? And surely they are, as a whole, false, though there are true things in them too.”

If you are like me, then at first this passage just seems like total nonsense. The key is that the word “music” used to mean “any activity inspired by the Muses”. Music, poetry, art, literature, myths, all of those things were conflated together, at least in the word itself and in the way Socrates talks about it here.

But it seems like in practice they would be conflated, too. It makes sense if you think about it - in a world with few books, you can’t really have literature as we know it today. You can, however, have epic poems like the Odyssey. But when you’re putting together an epic poem, the music might be just as important as the words.

Or in a world where the lawsuits weren’t settled by a judge as much as they were by a jury of 501 or more people, and instead of a lawyer you would commonly hire a speechwriter who would draw parallels to epic poems to make the case, because those epic poems are the main shared moral values in your society, there might be less of a difference between “studying law” and “studying music” than you might think.

Just imagine if you had to be a great musician, to be a great lawyer.

Nowadays it seems like music is basically just for entertainment. I wonder if we have lost something.

It’s a little crazy, but I can think of one case where music really helped in my education. The song Fifty Nifty United States. I memorized that thing in third grade and to this day I can still use it to reel off the names of all fifty states. My kids find this quite entertaining, because to them the names of the states are just nonsense words and they’re impressed by how much nonsense I can speak in one fell swoop.

What if there was an epic poem that taught you calculus? Just memorize this one epic poem, and if you forget how calculus works, no problem just sing that song to yourself until you get to the part about integrating by parts.

Might work better than drill and kill.

-

Socially Irresponsible Investors

It is sort of a shame how capitalism is clearly so powerful in the world, and we would like the world to be a good place where virtues like honesty and fairness and humility and justice are rewarded, and yet capitalism isn’t really fundamentally based on any of those things, it’s based on chasing after money. It can feel weird to believe in lots of virtuous things, and then invest your money in a way that ignores all that. So maybe there is some compromise where you overall try to invest your money intelligently, but somehow “slant” your investments towards things that are good for the world?

In general the name for this is socially responsible investing.

Socially responsible investors encourage corporate practices that promote environmental stewardship, consumer protection, human rights, and diversity. Some avoid businesses involved in alcohol, tobacco, fast food, gambling, pornography, weapons, contraception/abortifacients/abortion, fossil fuel production, and/or the military. The areas of concern recognized by the SRI practitioners are sometimes summarized under the heading of ESG issues: environment, social justice, and corporate governance.

This is probably a good thing, according to the Occamian logic of, trying to do good is generally good. You might make a little less money, since you’re less focused on profit, but it’s worth it because you make the world a better place. Financial markets are weird, though. I wonder if there is more to this sort of investing strategy.

In particular, I theorize the existence of the opposite type of investor: the socially irresponsible investor. The socially irresponsible investor actively seeks out investments that are making the world a worse place. They invest in companies that harm the environment, disregard consumers, break the law, ignore social justice. A socially irresponsible investor wouldn’t proudly issue press releases about their great strategy, so you wouldn’t naturally hear about this strategy, even if it were super-popular. So don’t disregard this theory just because you have never heard of such a thing.

Why would someone do this? Well, let’s try to model this. Let’s say there are three types of investor: the responsible investor, who is willing to make a bit less money in order to invest in companies that help the world. The neutral investor, who just focuses on which investments seem like good investments, and the irresponsible investor, who invests in precisely those companies that are evil, the ones that the responsible investor avoids.

Who makes the most money? Well, the whole point of responsible investing is that you’re willing to make a bit less money by having priorities other than making money. So you might expect the responsible investor to make a bit less money than the neutral investor. But the neutral investor’s strategy is basically an average between the responsible investor and the irresponsible investor. So… the irresponsible investor must be making the most money of all of them?

For what it’s worth, I wasn’t the first person to think of this. For example there was the Vice Fund which publicly tried to make this sort of evil strategy work.

Vice Fund, a mutual fund started 14 months ago by Mutuals.com, a Dallas investment company, is profiting nicely from what some would consider the wickedest corners of the legitimate economy: alcohol, arms, gambling and tobacco. So far this year, Vice Fund has returned 17.2% to investors, beating both the S&P 500 (15.2%) and the Dow Jones industrial average (13.2%) by a few points.

In fact, all four vice-ridden sectors have outperformed the overall American market during the past five years. “No matter what the economy’s state or how interest rates move, people keep drinking, smoking and gambling,” says Dan Ahrens, a portfolio manager at the self-described “socially irresponsible” fund.

It seems dangerous for the best moneymaking strategy to involve being evil. People who care a lot about money would come in, start looking around, realize the best strategy was evil, and evil behaviors would spread.

But honestly, I don’t think this model is accurate for the general stock market, because I don’t believe that any of these investors are doing better than monkeys throwing darts. Like more and more people nowadays, I am dubious of active stock-picking and personally aim for a pretty conservative investment strategy with lots of index funds.

For venture capital investing, though, I do believe that there are different types of investors and that their decisions are different than random guesses. There are certainly a lot of groups who are trying to be socially responsible investors in venture capital, focusing on women, underrepresented minorities, or some more-general notion of doing good:

-

The NYT says that Nancy Pfund of DBL Investors has “quietly built a reputation as the go-to venture capitalist for companies looking to make a social impact.”

-

The Women’s Venture Capital Fund “capitalizes on the expanding pipeline of women entrepreneurs leading gender diverse teams.”

-

City Light Capital “aims to generate strong returns while making a social impact.”

-

The Catalyst Fund was “established to invest in technology companies founded by underrepresented ethnic minority entrepreneurs.”

-

Solstice Capital “is committed to investing 50% of its capital in socially responsible companies that are currently not well served by the venture capital community.”

Well, that’s cool. So… are there socially irresponsible venture investors, who seek out the opposite sort of investment? Worse, are the irresponsible investors making more money?

I was going to put together a list with some bullet points, but I really don’t want to be calling people out and naming names, especially when really I know so little about the details here and this is more some idle abstract theory than a concrete proof. The convenient thing about venture capital, though, is that success is really defined by hitting a few winners, rather than performance of your median investment. So you can investigate yourself, look through the billion dollar club, and see how many of the most successful tech startups are famous for breaking the law, being run by social injustice warriors, helping the war machine, or “multiple of the above”. And see who invested in multiple of them, and come to your own conclusions.

Of course, I’m sure nobody would never write a blog post talking about how their socially irresponsible investing strategy was the key to their success.

-

-

Military Artificial Intelligence

There has been some discussion recently about artificial intelligence in military applications. In particular, Eric Schmidt posed an interesting theory:

I interviewed Eric Schmidt of Google fame, who has been leading a civilian panel of technologists looking at how the Pentagon can better innovate. He said something I hadn’t heard before, which is that artificial intelligence helps the defense better than the offense. This is because AI always learns, and so constantly monitors patterns of incoming threats. This made me think that the next big war will be more like World War I (when the defense dominated) than World War II (when the offense did).

To me, something doesn’t quite sit right about this. It feels like this is reasoning by analogy instead of reasoning from first principles. It seems like World-War-I-style defensive warfare happens when there is a fundamental advantage from sitting in one physical location, like in medieval times before artillery got powerful enough to defeat physical walls, rather than when patterns of incoming threats are easy to monitor.

Disclaimer: my expertise is not military. I did listen to Dan Carlin’s podcast on World War I though. Best 20-hour podcast ever.

So it’s not really fair for me to just snipe at Eric Schmidt. I should offer a theory of, what will artificial intelligence do to the military? What sort of military operation will it make more powerful?

I think the first question to ask is whether “offense and defense” is the right way to break down future wars. In World War I and World War II, you had an offense and a defense. Nowadays, the sides are more likely to be “the state” versus “the terrorists”. If you’re interested in this shift, a bunch of military types seem to refer to this as the rise of fourth-generation warfare.

Fourth-generation warfare (4GW) is conflict characterized by a blurring of the lines between war and politics, combatants and civilians.

The term was first used in 1989 by a team of United States analysts, including paleoconservative William S. Lind, to describe warfare’s return to a decentralized form. In terms of generational modern warfare, the fourth generation signifies the nation states’ loss of their near-monopoly on combat forces, returning to modes of conflict common in pre-modern times.

The first bits of AI in war are already happening, with the rise of drone warfare. So far, drone warfare is a big advantage for “the state”. While ISIS is using more and more drones, for now there’s still a massive AI advantage that goes to the side which can deploy more capital.

It’s not clear if this trend will continue, though. If drones get cheaper and cheaper, we could end up in a world where the state and the terrorists both have access to drones of similar quality. What would warfare look like if the terrorists had just as many Predator drones as the government, because the parts cost $100 and you can make them in any back alley with a 3D printer? If the drone was the size of a paper airplane, and you could give it a few pictures of any person and have it seek out the target? If assassinations were cheap on each side, the forces of chaos seem like they would rule the day. So at that point it seems like AI would be an advantage for the terrorists. It’s hard for me to imagine how any society could live under those conditions, really. What would society resort to in that world?

It seems like a recipe for totalitarian crackdown. Make 3D printers illegal, record video on every street corner, record video inside every house, track every object everywhere, it’s the only way to stay safe. If we have to go that far, then it seems like AI will be an advantage to the state. It’s the only way to make administration of the totalitarian state practical. Not really a pleasant world though. Hopefully something is wrong about my projection here.

Besides drones, I can imagine military AI becoming relevant for cybersecurity. This one is a bit more far out - we are a lot better at the AI you need for robotics, than the AI you need to hack into a computer system. So would AI be good for the black hats or for the white hats? I can imagine an AI that’s really good at finding flaws in a computer system, but I can also imagine that same AI scanning your defenses like a souped up Valgrind checking for the existence of any flaws. I guess I could see this going either way.

So overall, the military status quo is pretty good. The world is not devolved into warfare and chaos, and it seems nice to keep it that way. Unfortunately, it seems to me like military AI is quite likely to take things in the wrong direction. I don’t think there’s a practical way to get the world to not adopt a new military technology; the same arms race mechanic applies now as it did in 1914. Wish I had a way to end this post on a positive note, but maybe I should just leave the reader hanging with a vague sense of unease. Enjoy!